A Tribute to Don King

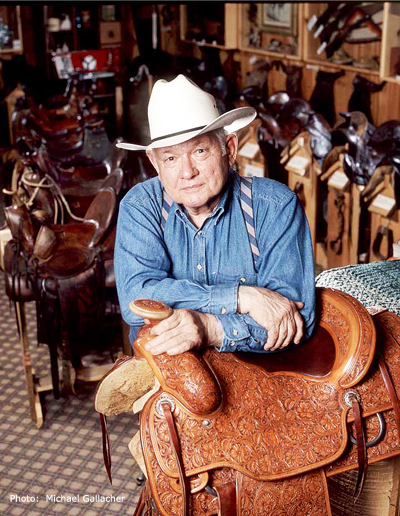

A special thanks to Michael Gallacher for providing the above photo for this tribute page.

more video clips below this article

Don King was born August 19, 1923, in Douglas, Wyoming, on the North Platte River about 100 miles north of Laramie. His father, Archie King, was a cowboy and itinerant ranch hand who traveled all over the Western United States. By the age of 14, King was beginning to support himself doing odd jobs on ranches and at rodeos, and trying to learn to tool leather in his spare time. Within a year, he was selling and trading belts, wallets, and various small gear of his own making. “Cowboys always trade,” King said. “I traded for pants, shirts, hats, spurs, anything. Sometimes I ended up with nothing.”

For years, King worked in saddle shops and on ranches in California, Montana, and Arizona before returning to Wyoming, where, in 1946, he married and settled in the town of Sheridan. There, he became an apprentice to his friend Rudy Mudra, an expert saddle maker, doing piecework and assisting in the building of saddles for the local cowboys. Later, King was able to acquire his own 200-acre ranch, where for several years he raised cattle and horses while working only part-time at the leather trade.

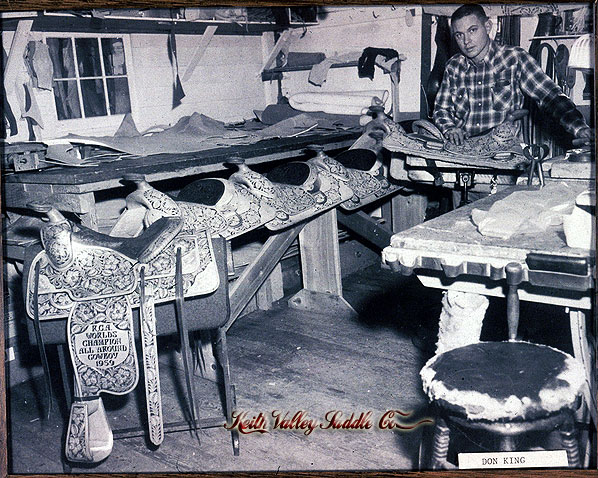

In 1957, King devoted himself full-time to saddlemaking and leather tooling, focusing primarily on highly ornamental trophy saddles, which are given as prizes in rodeo competitions. He developed his own style of tooling, characterized by wild roses with a distinctive shape (as though they were viewed from a 45-degree angle), arranged in complex, scroll-like patterns of interlocking circles.

King became known for his impeccable craftsmanship and incredible precision that were demonstrated in the making of what is now known as the “Sheridan-style” saddle, a type of saddle he is credited with almost single-handedly developing. The Sheridan-style saddle is, in its general form, a classic high plains roping saddle: short, square skirts; a low cantle with a broad Cheyenne roll; large swells and a prominent horn; small side jockeys; and relatively narrow fenders that are at a 90-degree angle to the skirt. King was one of several saddle makers who were responsible for the increasing popularity of this saddle, although its most distinctive element is the characteristic wild rose tooling he created. In addition, King used unusually deep stamping to give greater three-dimensional depth to his tooling and relied more heavily on the swivel knife to emphasize the lines of detail more than the shading.

By the late 1950s, King had established his reputation among ranchers and rodeo cowboys. Sheridan, where he lived, had been a center of the cattle industry since the late nineteenth century and has supported numerous leather workers and saddle makers. King’s apprentices have included a number of top-notch saddle makers, including Billy Gardner, Chester Hape, and Bob Douglas. His sons, Bruce, Bill, Bob, and John, have all become accomplished leather toolers.

Over the years, King’s saddles have been acquired by working cowboys and celebrities alike, such as Queen Elizabeth, Ronald Reagan, and the Crown Prince of Saudi Arabia. He has made trophy (prize) saddles for virtually every rodeo event, working regularly to meet the needs of the PRCA (Professional Rodeo Cowboys Association). His work has been exhibited widely in museums and festivals, such as the Edward-Dean Museum of Decorative Arts (Cherry Valley, California), the Nicolaysen Art Museum (Casper, Wyoming), and the Pro Rodeo Hall of Fame (Colorado Springs).

Thank you Don King...

for bringing this Extraordinary art

into our world!

Sculptors in Leather

by: Jane and Michael Stern

THE saddlemakers of Sheridan, Wyoming, carve leather with finesse on the order of skills like gunmetal engraving and scrimshaw. The saddles they produce are majestic creations -- fantastic to see, wondrous to touch, and delicious to smell. One could ride in them all day, rope big steers off them, winter with them in Montana's Judith Basin, and they would stay strong for years. But they are more than durable; they are bas-reliefs in leather, flaunting fields of flowers, curling vines, and leaves that run deep into the surface of the honey-colored hide. As Frank Lloyd Wright might have said, the carved bower is not on the saddle, it is of it. The surfaces of the saddles are stitched and layered with a surgical precision that makes the different components -- horn, pommel, seat, skirt, fender, stirrups -- appear to be organic parts of a single whole. Whether viewed from the ground or from horseback, these saddles look like flows of sculpted leather made to hug an equine back and be hugged by a rider's thighs. Silver-dollar-size conchas or corner plates may adorn the leather skirts of the saddles. They, too, are embellished with detail, wrought in gold: bucking cayuses, hearts, and flowers.

A working cowboy's livelihood -- and his very life -- depends on a saddle that is comfortable, strong, and functional. The old folk song "Chisholm Trail" tells of a cowboy with a "ten-dollar horse and a forty-dollar saddle"; it is still true that horses come and go but a really good saddle will last a man a lifetime.

About a hundred years ago saddles were elevated from cowhands' working tools to dream objects that signified the frontier. Thanks to the romantic image of the West created by mythmakers as varied as Teddy Roosevelt, Buffalo Bill Cody, and the railroad magnate Fred Harvey, and also to a spate of pop-culture frontier heroes in books and weekly magazines, cowpunchers began to see themselves -- and their gear -- as the embodiment of freedom, independence, and adventure. Saddle shops, which had grown up throughout the West wherever the cattle business went, issued catalogues showing saddles far more handsome than any working ranch hand needed. The catalogues came to be known in the cowboy fraternity as bunkhouse bibles, and were studied and memorized by men for whom their contents were fantasies.

Long waits have always been part of the experience of acquiring a deluxe custom saddle. Most of today's top saddlemakers are at least a year or two behind in filling orders; one esteemed craftsman in northern New Mexico, a veteran carver well into his seventies, tells his new customers that the wait is ten years. The Montana cattle rancher Jim Hamilton wrote a poem called "The Rancher's New Saddle," in which he wryly described a harrowing two years of watching calf prices go down after he ordered an expensive saddle from Sheridan's legendary Don Butler. The poem ends with the rancher in his banker's office, getting a loan to pay for his prize.

The banker says, "What! Don Butler made it?"

Then he leans back in his chair with a smile.

"It still ain't real funny, but we'll loan you the money.

You may go broke, but at least you got style!"

The frustration is often compounded by the quirky nature of saddlemakers, who tend to be better artists than businessmen. Legend has it that one Sheridan saddlemaker used to take an order patiently, writing down everything a customer wanted -- stirrup size, cantle angle, horn shape, and the like. Two years later he would deliver a saddle that he had made just the way he wanted. The punch line is that no one ever refused a saddle he delivered -- it was too beautiful.

THERE was certainly nothing pretty about the earliest western stock saddles, which were scarcely more than wooden frames covered with leather ponchos. Cowboys who made the historic cattle drives north from Texas into Kansas and then up to the high plains were known for riding saddles that were big, tough, and plain. By the late 1870s cattlemen were pushing north of Cheyenne and grazing beef in the Big Horn basin, where the town of Sheridan soon became the main stop on the rail line. Though it was a dirt-street cow town, with its share of rough-around-the-edges frontier life, Sheridan was different from most range settlements. Many of the big cattle ranches in the area were owned by English aristocrats who had migrated to America to be closer to their holdings; what would become one of America's oldest polo fields was built near Sheridan in 1898. Local horse farms began to breed thoroughbreds for sport as well as quarter horses for cowpunching. Eatons' Ranch, along Wolf Creek eighteen miles from town, opened in 1904. One of the first dude ranches in the country, it quickly became the largest. Well-heeled Americans seeking a taste of cowboy life headed to Eatons' or other local guest ranches, such as Spear-O-Wigwam, Bones Brothers, and Horton's H F Bar.

The popularity of the West was largely owing to the salesmanship of Buffalo Bill Cody, who in 1883 started thrilling crowds across America and the world with his Wild West show, which featured riders outfitted with deluxe western regalia much fancier than what any working cowhand would use. The show's gilded image of the frontier was so persuasive that buckskin fringe and tack with ornate tooling became part of the region's culture, inspiring genuine cowboys and dudes alike.

A required stop for enthusiastic dudes vacationing in Big Horn country was the saddle shop of Otto F. Ernst, which was a fixture in downtown Sheridan from 1902 to 1975, selling jeans, checkered shirts, cowboy boots, hats, and -- to serious dudes -- sumptuous Ernst saddles. Saddlemakers had worked in Sheridan since 1890 (every cattle town needed someone who could manufacture and repair tack), but the panache of Ernst's saddles put Sheridan on the map. Those he sold weren't just tools. With their floral carvings, they were handsome souvenirs of the Cowboy State. Ernst marketed them accordingly, choosing names for his various models that evoked the cowboy spirit, such as the Barkey (after Roy Barkey, a rodeo star) and the Gollings (after the Western artist E. W. Gollings). He became known for his enticing catalogues and his calendars depicting cowgirls on horseback outfitted with stunning Ernst tack; traveling in his Dodge truck, he took orders from Texas to South Dakota and from Oklahoma to California.

ALTHOUGH Ernst's saddle shop is no longer in business, Sheridan is still the best place in the West to order a high-grade custom saddle. You can make an appointment with one of the artisans in and around town, or you can simply wander into King Saddlery, on Main Street, the best-known and most respected saddlery on the high plains -- so grand that when Queen Elizabeth came to Sheridan a few years ago to see friends nearby (descendants of the ranchers who settled the Wyoming Territory), she visited the shop. Each Labor Day the town celebrates "Don King Days," a long weekend of old-fashioned roping and riding contests and polo matches.

King, who is seventy-four (at the time this article was published back in 1998), speaks with a quiet voice, in the kind of level, self-assured tone that puts a nervous horse or a skittish cow at ease. He long ago gave up riding, because his knees had been wrecked by wild broncs, but he still looks like the quintessential cowboy. His hands are magnificent: strong and tough from years of hard ranch work, yet absolutely precise when he offers a handshake or points to an interesting feature of a saddle.

King first practiced his craft by turning scrap leather into wallets and belts for cowboys he knew and for tourists at the western dude ranches where his father worked. One winter in the late 1930s, when his father was working at the D Bar H guest ranch, in Palm Springs, King found some space in the back of a local saddle shop, where he made belts and other small leather items with a wild-rose pattern. He sold twenty-five of his belts to a guest at the D Bar H, Jack Kriendler, a co-owner of the New York club 21. When Life magazine ran a feature about dude-ranch fashions, the story included a picture of a lady friend of Kriendler's wearing one of the belts. At the time southern California was something of a leather crafter's paradise, thanks partly to the fancy tack that movie cowboys used. One day Edward Bohlin walked into the shop. Bohlin was America's most famous saddlemaker, a full-fledged celebrity who made the silver-bedecked saddles used by Tom Mix, Gene Autry, and Roy Rogers. He was so impressed by the young King's finesse with leather that he offered him a job on the spot. "I didn't take it," King told us when we visited him. "When you work in another man's shop, you work in his style. I wanted my own name."

King was fifteen years old at the time. In a trade in which apprenticeship is the only way to get ahead, his refusal was audacious. He went to Montana, where he took a job as a ranch hand and used his spare time to carve leather. In the early 1940s King worked off and on at Rudy Mudra's saddle shop in Sheridan. When he returned from the war, he went back to work for Mudra on the condition that Mudra teach him how to build a saddle.

In 1947 King opened his own saddle shop in Sheridan. From the beginning he had more work than he could handle. But he soon closed the shop, unhappy to be confined to a bench. "Twice in my life I swore I would never build another saddle," he told us. "I preferred to break horses for a living."

King still carved leather when he had the chance, doing custom jobs and occasional piecework for other saddlemakers in Sheridan and Billings. His spare-time carving was already influential. William Gardner was thirteen years old when he started to apprentice with King. Today he is one of the acknowledged masters of the Sheridan style. The two met when King, at seventeen, went to break horses at the Neponset Stud Farm, where Gardner's father was the top hand. King showed Gardner how to make his own tools and how to cut elaborate patterns deep into the hide. "We've worked together like brothers and fought like brothers ever since Don came out to the ranch," Gardner told us. "Don's son John apprenticed with me when he began." It has been said that King and Gardner could each make half of one saddle and no one could see the difference. Yet when one compares saddles that each man has made independently, there is no mistaking their different styles. King's flowers are tight and coiled, their energy contained; Gardner's are lush, spreading, and deep. The difference is subtle, like that between artists' brushstrokes.

King is reluctant to call his work art. It sounds too prissy for something as tough as the saddles he has made. Although he has won a National Endowment for the Arts grant and many other accolades for his work, he prefers to call himself a mechanic. "They have tried to put the art thing onto saddles," he told us. "But to be a saddle craftsman you first have to be a good mechanic."

KING formally retired about ten years ago (from the time that this article was published 1998), although even today he keeps up his leather-carving skills. His place at the bench has been taken by his son John, a former rodeo cowboy, who is now the saddlemaker; another craftsman, Jim Jackson, also works at King Saddlery. We watched John King transform a plain strip of leather into a magnificent belt. The small basement shop where he works is perfumed by the sweet, earthy aroma of tanned hide. King handles the leather with casual delicacy, pulling it across his palm, running his fingertips over the surface, positioning it on a cool marble block. Before it is carved, a piece of leather is wetted and then partially dried, to make it pliant. King stamps a line, straight or curved, into it and then, like a painter with a fine brush, wields a swivel knife to deepen and extend the line and give it shape. Finally he takes a stamping tool -- nothing more than a nail or a quarter-inch bolt with a pattern that has been filed and ground into one end -- and holds it against the cut leather as he whacks it with a mallet to create a furrow. Curve by curve, line by line, the design in his mind travels through the tools in his hands to the leather.

Jane and Michael Stern are the authors of Way Out West (1993); Happy Trails: Our Life Story (1994), with Roy Rogers and Dale Evans; and Dog Eat Dog (1997).